“In 1908, more than 30 denominations representing over 18 million American Protestants set their doctrinal differences aside and met in Philadelphia at what is called the Federal Council of Churches. Their great concern was not the Gospel, but how to address the social issues of the day: race relations, international justice, reducing armaments, education, and regulating the consumption of alcohol. This was the beginning of the modern ecumenical movement.”

“In 1908, more than 30 denominations representing over 18 million American Protestants set their doctrinal differences aside and met in Philadelphia at what is called the Federal Council of Churches. Their great concern was not the Gospel, but how to address the social issues of the day: race relations, international justice, reducing armaments, education, and regulating the consumption of alcohol. This was the beginning of the modern ecumenical movement.”

(Mike Riccardi – The Cripplegate) One of the most devastating attacks on the life and health of the church throughout all of church history has been what is known as the ecumenical movement—the downplaying of doctrine in order to foster partnership in ministry between (a) genuine Christians and (b) people who were willing to call themselves Christians but who rejected fundamental Christian doctrines.

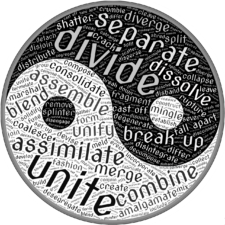

In the latter half of the 19th century, theological liberalism fundamentally redefined what it meant to be a Christian. It had nothing to do, they said, with believing in doctrine. It didn’t matter if you believed in an inerrant Bible; the scholarship of the day had debunked that! It didn’t matter if you believed in the virgin birth and the deity of Christ; modern science disproved that! It didn’t matter if you embraced penal substitutionary atonement; blood sacrifice and a wrathful God are just primitive and obscene, and besides, man is not fundamentally sinful but basically good! What mattered was one’s experience of Christ, and whether we live like Christ. “And we don’t need doctrine to do that!” they said. “Doctrine divides!” Iain Murray wrote of that sentiment, “‘Christianity is life, not doctrine,’ was the great cry. The promise was that Christianity would advance wonderfully if it was no longer shackled by insistence on doctrines and orthodox beliefs” (“Divisive Unity,” 233).